AI is fuelling a poverty of imagination ⊗ Why nothing about AI is inevitable

No.376 — Fungi as your Futurist ⊗ Offshoring automation ⊗ Solid state batteries for electric vehicles ⊗ Fast and tiny probes for interstellar travel

AI is fuelling a poverty of imagination

For some reason, I’m always drawn to pieces and reflections about AI in education. I think it’s because, although I haven’t spent much time in higher ed, my job is kind of to learn things and that’s supposed to be the place for learning things? I’m also wondering if it doesn’t have to do with ROI, meaning that discussing AI in any other fields quickly turns to ROI and the specifics of the work the writer is involved in. It’s less prevalent in thinking about AI in education. Or at least, the goal seems to be worthier (better education) than in other places (productivity).

The piece features sociologist, professor and cultural critic Tressie McMillan Cottom and an Opinion writer for The New York Times, Jessica Grose, discussing AI in higher education. McMillan Cottom describes AI as “mid tech,” both in the sense that it averages midlevel responses and that it’s not as transformative as promised. She argues AI sits in a long line of hyped educational technologies (TV, typewriters, tablets) that fail to connect to learning outcomes or address risks to student development—by the way, as I’ve mentioned before, if edtech interest you, diving into Audrey Watters’ archives is mandatory. The main problem is that AI’s promotion in schools rests on the simple premise that “it’s happening, so students need to know it,” rather than on evidence it improves education. McMillan Cottom points out that most proposed uses boil down to automating mundane tasks, but the case for AI in education lacks substance when measured against what education is supposed to do.

On the humanities specifically, both participants see few legitimate use cases. Grose explains that AI might help with pattern recognition in medical research, but for humanities work, the technology undermines the cognitive process itself. Writing and thinking are too specific to individual needs—AI can’t determine what’s important to an argument before the writer has read and thought through the material (see below). Their conversation emphasizes that AI strips away the mistakes and serendipitous discoveries that form the foundation of learning. McMillan Cottom describes this as a “poverty of imagination” about human capacity, where the emotional feedback loops that enable learning—pride, risk, failure—get eliminated. The technology makes mundane tasks automatic but hollows out the basic skills that serve as steppingstones to higher-order thinking. Both argue this makes educators more necessary, not less, though society seems unwilling to make that investment.

I agree with everything they say, except the level of usefulness AI can provide. To take a simple task; summarising an article with AI instead of reading it does not provide the learning experience a thorough reading does. However, summarising and questioning after reading it can then provide value. I think many critics of AI take the very simplest version of an AI task that they can, and then argue against that. While proponents will ignore flaws so that everything looks fantabulous. Contrary to the label “mid” above, here standing somewhere in the middle and critiquing while giving proper thought to the current use and potential is, to my mind, the correct place to be.

She didn’t outright ban the use of A.I. in her class, which I thought was also really interesting. She had the students discuss among themselves what they thought would be appropriate and come up with a code of conduct that they all agreed to stick to. […]

And I do think if we have to have a positive outcome of this new technology, it’s that I hope it forces educational systems to sit back and say: What are the values we are trying to inculcate in these students? What are — why are we here? What do we hope that they learn? What do we hope is happening in the classroom? […]

I think [the students] actually want more guardrails. I think they are craving the positive feelings that come along with learning, but they aren’t supposed to be able to resist it. […]

Perhaps one of the biggest threats that A.I. poses to education isn’t that it’s going to make educators useless, but that it is going to make educators so much more necessary than we are willing to invest in.

A.I. actually makes it more important that we have everything from librarians to counselors to teachers to professors to researchers who can put this rapidly changing information environment into context and can develop the capacity in students to make sense of things.

Why nothing about AI is inevitable

I don’t do this often but here is a second piece on AI and a second interview transcript. In this one, historian Mar Hicks explains why nothing about AI is inevitable. She argues that claims about AI’s inevitability function as marketing tactics designed to create hype and ultimately deskill jobs. Hicks points out that hype cycles center on tools rather than processes because tools are easier to sell “it’s much harder to explain and mobilize excitement around processes and infrastructures and knowledge bases.” When critics, within their analysis, concede that a technology might be inevitable, they’re already arguing from a weaker position, one that assumes technologies shape society rather than the reverse. This technologically deterministic thinking concentrates power in the hands of those who make and sell the technology.

Hicks also connects AI to an extractive pattern in computing history where technology adoption serves to centralize power among those who already have it, allowing them to bypass labor and domain knowledge. Hicks describes how computing systems have historically been tied to state power and control, though this history gets obscured by the presentation of technology as personal consumer products. The solution can’t be technological—technologies always create more problems that require more technological fixes. What’s needed are political, social, and economic responses that restore power to people rather than concentrating it in machines and their makers. → 🗄️

Another way of gaming the system, which I would argue is more dangerous, is to promise something that you either know you can’t deliver, or you’re not sure that technology can deliver, but by trying to essentially reengineer society around the technology, reengineer consumer expectations, reengineer user behaviors, you and your company are planning to create an environment—a labor environment, a regulatory environment, a user environment—that will bring that unlikely thing closer to reality. […]

Whenever something is framed as new and exciting, be very wary about just uncritically adopting it or experimenting with it. Likewise, when something is being presented as “free,” even though billions of dollars of investment are going into it and it’s using lots of expensive resources in the form of public utilities like energy or water. […]

Instead of just saying “AI is like a calculator, it’s just a new tool, get over it,” maybe we should be comparing it to automated looms and automated weaving, and thinking about how that affected labor, and how frame breakers—Luddites—were coming in and trying to get this technology out of their workplaces, not because they were against technology, but because it was a matter of their survival as individuals and as a community. […]

This work was anything but unskilled. Now we have work that is assumed to be unskilled—and has historically been done by women—being marketed as replaceable by AI: using chatbots to virtually attend or take notes of meetings, to automate tedious tasks like annotating and organizing material, to write emails, reports, code.

Futures, Fictions & Fabulations

- Fungi as your Futurist. “If we are to solve some of humanity’s most radical challenges, we need radical new ways of thinking. Fungi as your Futurist is a first-of-its kind playbook for regenerative futures, inspired by nature’s intelligence.”

- Unscripted 2025 Episode 1 with Keolu Fox & Lonny J Avi Brooks. “In Episode 1, Indigenous futurist Keolu Fox, PhD, associate professor at UC San Diego and co-founder of the Native BioData Consortium, sits down with ancestral futurist Lonny J Avi Brooks, PhD, professor and chair of communication at Cal State East Bay and co-founder of AfroRithm Futures Group.”

Algorithms, Automations & Augmentations

- Offshoring automation: Filipino tech workers power global AI jobs. “Tele-operation of robots allows physical labor to be offshored. The Philippines is seeing steady hiring by global companies for AI-related IT service and tech jobs. Filipinos are paid less than their counterparts in the developed world, and worry they will lose their jobs to automation.”

- A quote from Geoffrey Litt. “Personally, I'm trying to code like a surgeon. A surgeon isn’t a manager, they do the actual work! But their skills and time are highly leveraged with a support team that handles prep, secondary tasks, admin. The surgeon focuses on the important stuff they are uniquely good at.”

Built, Biosphere & Breakthroughs

- “Toasterlike” process recovers rare earths from e-waste. “Compared with existing methods to recover rare earth elements, a process based on rapidly heating waste magnet material in the presence of chlorine gas uses one-third of the processing steps, reduces energy consumption by 87 percent, and produces 84 percent fewer greenhouse gas emissions.”

- How close are we to solid state batteries for electric vehicles? “These new solid-state cells are designed to be lighter and more compact than the lithium-ion batteries used in today’s EVs. They should also be much safer, with nothing inside that can burn like those rare but hard-to-extinguish lithium-ion fires. They should hold a lot more energy, turning range anxiety into a distant memory with consumer EVs able to go four, five, six hundred miles on a single charge.”

Asides

- Fast and tiny probes for interstellar travel. “In contrast, the new generation of starship designs are tiny, and they have no drives at all. The spacecraft have a mass of a few grams each. They’ll be accelerated out of our solar system by ground- or space-based lasers, traveling at an estimated 0.2c. … One version of this small-and-fast approach calls for sending a swarm of these puny flyers to the Proxima Centauri b exoplanet. Data would be returned by having the swarm emit light pulses in synchrony, detectable by telescopes on Earth.”

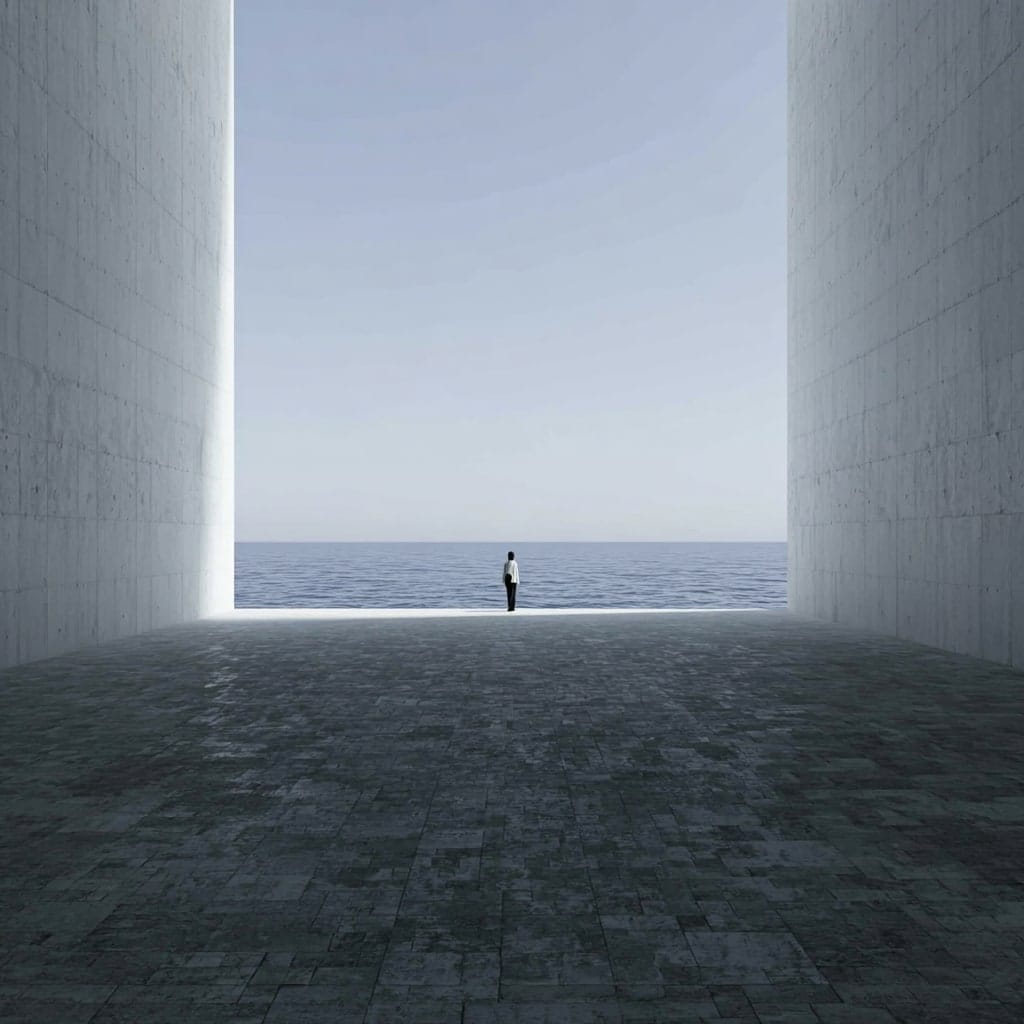

- Real photos that look fake. “I’ve seen a bunch of these before, but it’s cool to scroll and get your tiny mind blown over and over again. Human cognition and perception is such a trip.”

“Ambitious, thoughtful, constructive, and dissimilar to most others. I get a lot of value from Sentiers.”

If this resonates, please consider becoming a supporting member—it keeps this work independent.